The inside of a curve

Hi, I am shuba, and I'll be using this blog to dicuss various computer graphics topics I find interesting. I might also disgress on C++, which is my main programming language.

For my first article, I'll try and answer a question that's not as simple as it seems: onto what did I click? How did the program know what I clicked on? We're used to be able to click on various kinds of button, rectangular or circular. But when using image editing software such as The Gimp or Inkscape, we want to select the freeform shapes we create.

Connex components

The shapes in question are delimited by freeform curves which are drawn by the user. But how does a curve define a region? To answer this question, let's dive into topology.

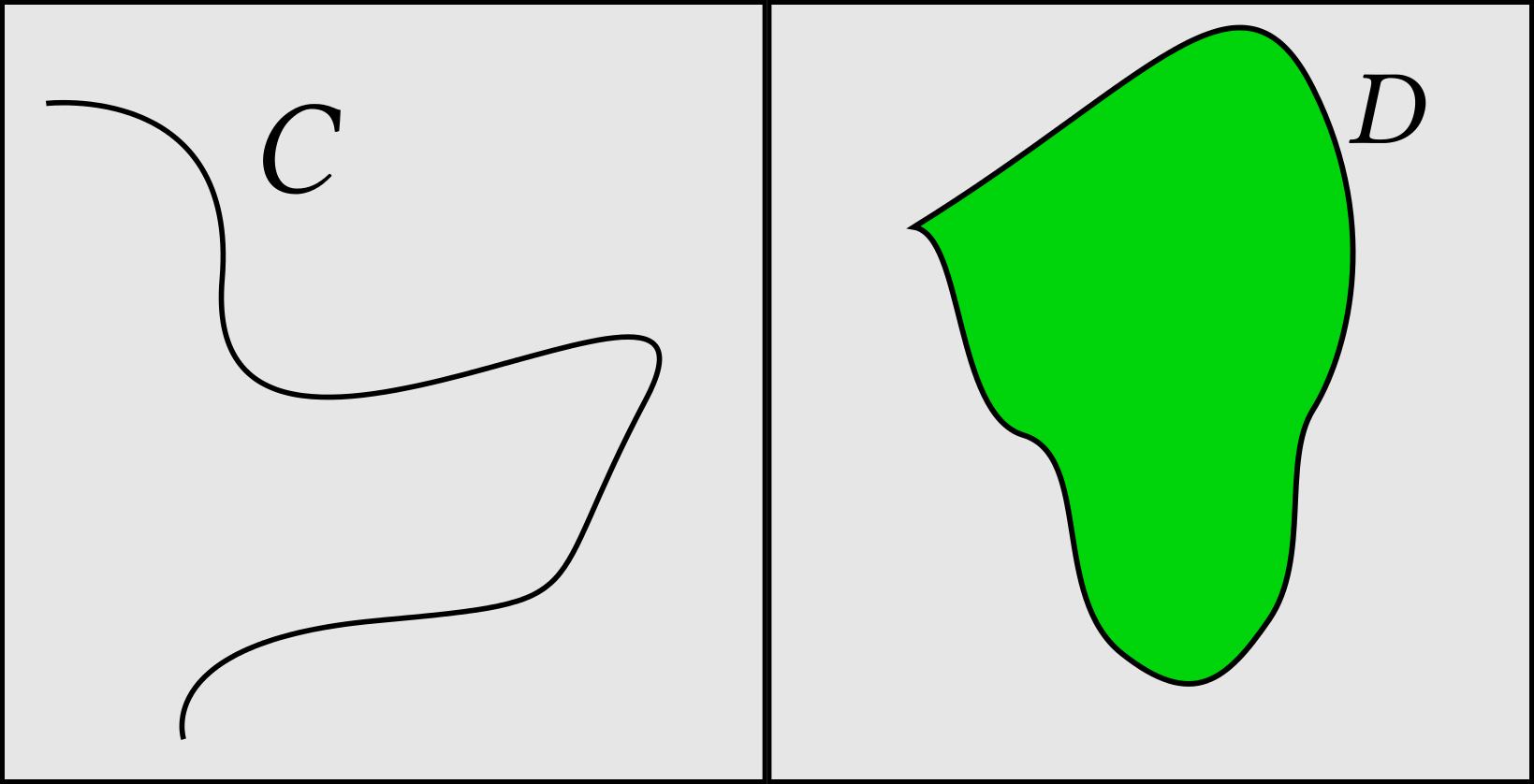

A subset of the plane is connex if any two points in that set can be joined by a continuous line lying in that set. Let's consider a curve C, and the set S containing the points of the plane that don't belong to C. The curve defines a region if and only if S is not connex. The following picture shows a curve C which does not define a region, and a curve D which defines one.

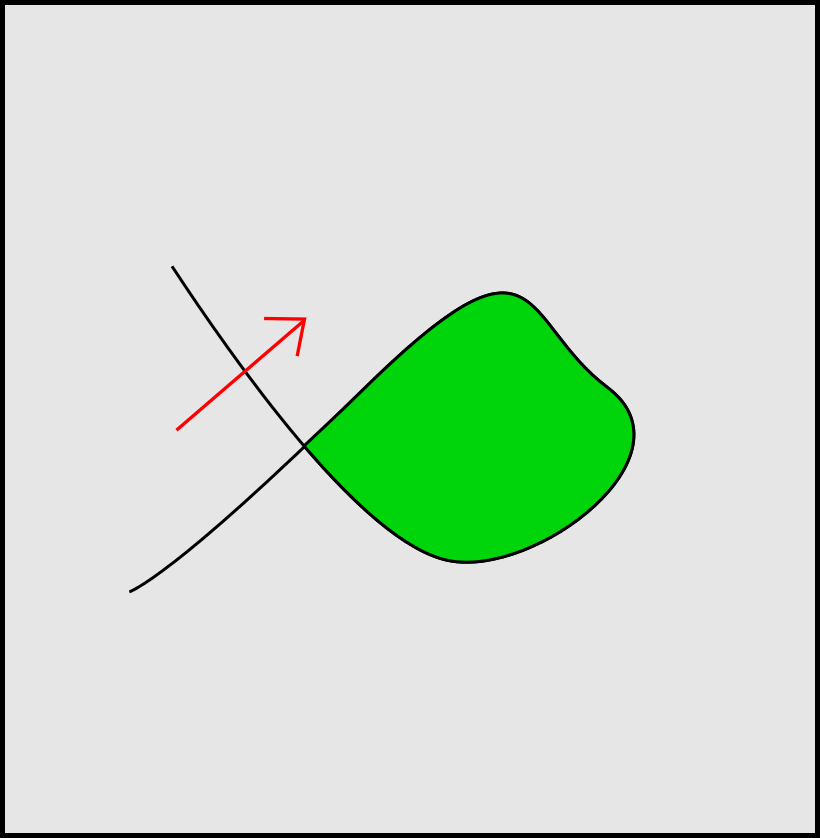

One can notice the second curve is closed. It turns out being closed, though not necessary to define a region, is crucial if we want to define a coherent notion of interior. Going through the curve should bring from the interior to the exterior and vice versa. But this can not be achieved with an open curve, as the following picture shows: the red arrow crosses the curve but both its start and its end belong to the same connected component.

Inside a curve

We can now define the inside of a curve. Any [1] closed curve with no self intersections (a simple closed curve) splits the plane into at two closed components, one of which has no finite bounds. The bounded component is the interior of the curve.

Let's shoot lines

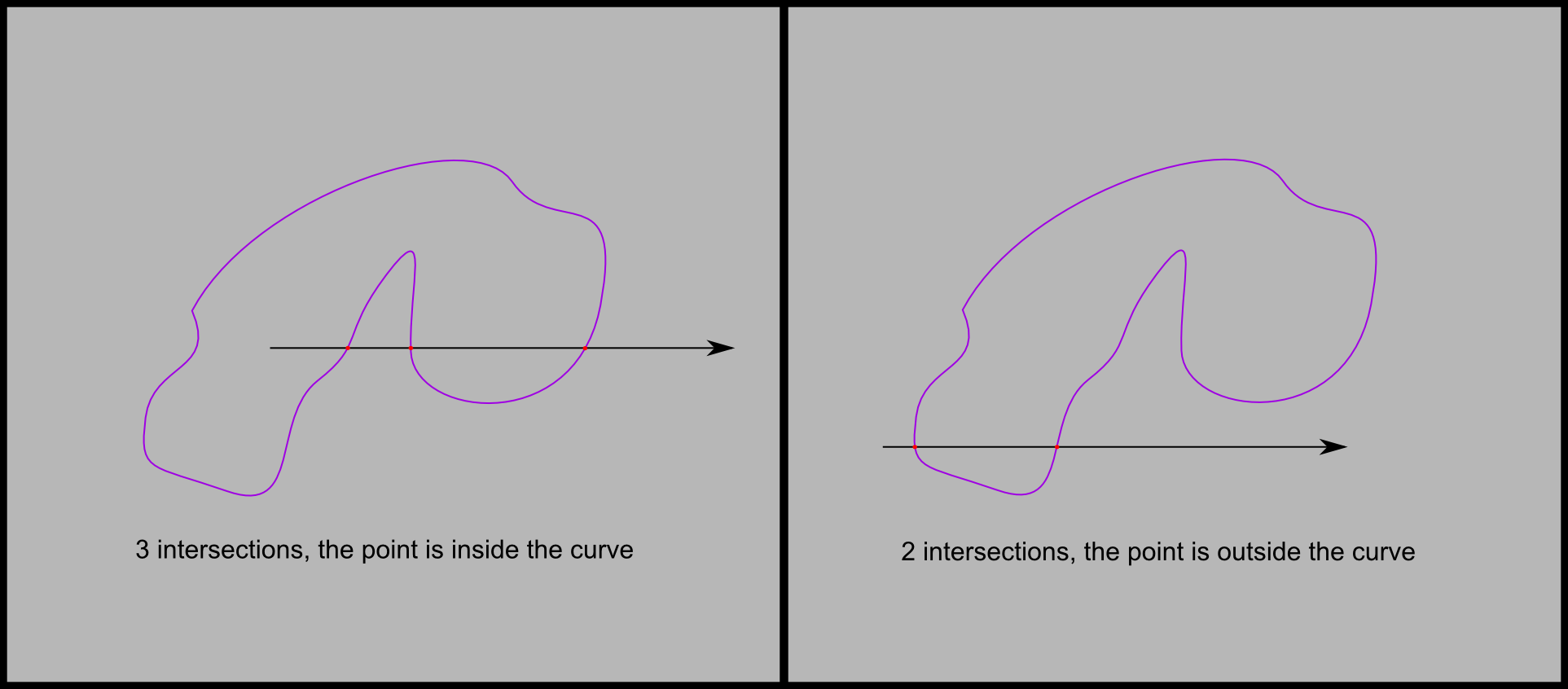

Now it's easy to devise a method to tell whether a point lies inside a curve. As we've seen, crossing the boundary of the curve means going from the inside to the outside (and vice versa). So if we pick a half-line starting at our query point, and count its intersections with the curve, we have our answer. If the number of intersections is odd, the query point is in the curve, if it's even we're outside the curve. That number of intersections is known as the winding number.

Intersecting a curve with a line

Ok, that's great, but how do we compute these intersections? It turns out there is a convenient analytical approach. Lines are represented by their equation (ax + by +c = 0). So given any paramteric curve (C(t) = (x(t), y(t))), we only need to find all t such that (ax(t) + by(t)+ c = 0). This method is particularly interesting if, as is often the cas, C is a Bézier curve, which means we need to find the roots of a polynomial. Cubic Bézier curves are widespread, and polynomials of degree 3 can be solved analytically.

Self intersecting curves

Unfortunately, curves might self intersect, and there's no clear answer to how to interpret the winding number. There are two competing rules, the even odd fill rule, which simply extents the previous approach, and the non zero fill rule, which considers oriented intersections between the curve and the line, counting one orientation positive and the other negative. Points with non zero winding numbers are inside the curve.

I'll get back on these fill rules in another post.

[1] Any continuous closed curve, if you're peeky...